Published: 11 November 2019 Author: Stefan Talmon DOI: 10.17176/20220122-155946-0

The conflict over Kashmir dates back to August 1947 when the predominantly Hindu State of India and the Muslim State of Pakistan were created out of colonial British India. At the same time, the paramountcy of the British Crown over the princely states of the Indian subcontinent and its treaty relations with them came to an end. The princely states were free to decide their own future. In October 1947, the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir with a majority Muslim population, but ruled by a Hindu maharajah, decided to accede to the Hindu-dominated Indian Union. In the run-up to the accession decision parts of the Muslim population of the state had revolted against the maharajah and a large force of Pakistani tribesmen had invaded Jammu and Kashmir and was moving on the state capital of Srinagar. It was at that moment that the maharajah decided to accede and appealed to India for assistance. On 27 October 1947, Indian troops landed in Srinagar and the first Indo-Pakistani war over Jammu and Kashmir ensued which ended only 27 July 1949 with the signing of a cease-fire agreement between the two States. The cease-fire line, which is also referred to as the “line of control” is supervised to the present day by the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP). India and Pakistan fought three more wars over Jammu and Kashmir in 1965, 1971 and 1999. In addition, since 1989 the state has witnessed an armed revolt against Indian rule which left tens of thousands dead and forced India to deploy hundreds of thousands of troops to the territory to quell it, making it one of the most militarized areas in the world.

Between 1948 and 1971, the United Nations Security Council adopted 18 resolutions addressing the territory. These resolutions envisaged, inter alia, that the question of whether the State of Jammu and Kashmir was to accede to India or Pakistan was to be decided by the residents of the territory in “a free and impartial plebiscite” conducted under the auspices of the United Nations. Although the Security Council decided “to remain seized of the matter and to keep it under active consideration” no formal meeting on the Kashmir conflict has been held and no resolution has been adopted since December 1971 due to the division of the permanent members over the subject. The only mention of Kashmir in a Security Council resolution since was in June 1998 when the Council urged India and Pakistan in general terms to resume dialogue on all outstanding issues between them, including Kashmir.

Both India and Pakistan claim the entirety of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. China also lays claims to certain pars of the state. India controls approximately 55% of the territory, Pakistan controls approximately 30% of the territory, while China controls the remaining 15%, including a part ceded to it by Pakistan.

Both India and Pakistan speak of the territory controlled by the other as Pakistan or India occupied or administered Jammu and Kashmir, respectively.

When acceding to the Union of India in October 1947, the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir gave up its control of communications, defence and foreign affairs, but preserved its autonomy in all other matters. The state of Jammu and Kashmir, as the only state in the Indian Union, was allowed to have its own constitution. This special autonomous status was formalized in Article 370 of the Indian Constitution of 26 November 1949 which was headed “Temporary provisions with respect to the State of Jammu and Kashmir.” The article exempted the territory from the application of the Indian Constitution, with the exception of Articles 1 and 370, and restricted the power of the Indian Parliament to make laws for the territory. Other provisions of the Constitution could be made applicable to the state of Jammu and Kashmir by Order of the Indian President either in consultation or with the concurrence of the Government of that state. Clause (3) of Article 370 expressly stipulated that the Indian President could, by public notification, declare that Article 370 should cease to be operative or should be operative only with such exceptions and modifications and from such date as he would specify provided that the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly of the state should be necessary before the President issued such a notification.

In 1954 the President of India, with the concurrence of the Government of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, made the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order in exercise of the powers conferred by Article 370(1)(d) of the Constitution. In that Order the Constitution was generally made applicable to the State of Jammu and Kashmir but with wide-ranging exceptions and modifications. In particular, the Jammu and Kashmir state legislature was empowered to define “permanent residents” of the state and provide special rights and privileges to those permanent residents. These included the ability to purchase land and immovable property, to vote and contest elections, to seek government employment and to enjoy state benefits such as higher education and health care. By these measures the state legislature was able, inter alia, to exclude Indians from outside the territory and thus preserve the demography of the Muslim-majority state.

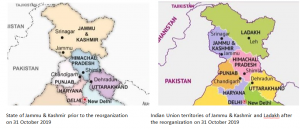

On 5 August 2019, the Indian President, in exercise of the powers conferred by Article 370(1)(d) of the Constitution, passed the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 2019 which made all the provisions of the Constitution without exceptions or modifications applicable to the state of Jammu and Kashmir and thus abolished the special semi-autonomous status of the territory. In particular, the move opened up the possibility of non-Kashmiris to acquire residency and property in the territory. The Order was published in an extraordinary issue of the Gazette of India and came into force at once. On the same day, the Indian Government introduced a Resolution for Repeal of Article 370 of the Constitution and the Jammu & Kashmir (Reorganisation) Bill, 2019 in the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Parliament of the Indian Union. The latter provided for the division of the state into two Union territories – Jammu and Kashmir, governed by a lieutenant governor and a unicameral legislature, and Ladakh, which was to be ruled directly by the central government without a legislature of its own. Both documents were adopted by the Hindu-dominated Indian Parliament with a majority of more than two-thirds, and the reorganization of the territory became effective on 31 October 2019.

The abrogation of the special constitutional status of Jammu and Kashmir by India’s Hindu nationalist-led government and the integration of the Muslim-majority region with the rest of the country was preceded by a massive security clampdown with the deployment of some 180,000 additional Indian troops to the territory, a complete communications blackout (suspension of landlines, mobiles and internet) and a round-the-clock curfew preventing the free movement of people, as well as hampering their ability to exercise their right to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression, and restricting their rights to health, education and freedom of religion and belief. Hundreds of Kashmiri political and civil society leaders were placed under house arrest or were detained on a preventative basis and were transferred to prison and detention centres outside the territory. There were also reports of excessive use of force by the security forces against Kashmiris protesting against the change of status. This led the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights to express concern about the human rights situation in the region. In a press briefing on 29 October 2019, the spokesperson for the High Commissioner stated:

“We are extremely concerned that the population of Indian-Administered Kashmir continues to be deprived of a wide range of human rights and we urge the Indian authorities to unlock the situation and fully restore the rights that are currently being denied. […]

Meanwhile, major political decisions about the future status of Jammu and Kashmir have been taken without the consent, deliberation or active and informed participation of the affected population. Their leaders are detained, their capacity to be informed has been badly restricted, and their right to freedom of expression and to political participation has been undermined.”

Pakistan, which also lays claim to the territory, strongly protested the Indian measures. It accused India of seeking to “willfully undermine the internationally recognized disputed status of Jammu and Kashmir”, “change the demography of Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir with a clear objective to undermine the United Nations plebiscite envisaged in the relevant Council resolutions”, and “deny the inalienable right to self-determination to the Kashmiri people.” Pakistan considered the constitutional changes to amount to the “illegal annexation of the disputed territory, in gross violation of international law.”

India, on the other hand, claimed that the constitutional changes were “driven by a commitment to extend to Jammu and Kashmir opportunities for development” that were earlier denied by Article 370 of the Constitution. The changes were “also expected to result in an upswing of economic activity and improvement in the livelihood prospects of all people of Jammu and Kashmir.” India, for its part, accused Pakistan of “cross-border terrorism” in Jammu and Kashmir, and of “supporting terrorism” and inciting “separatist activities” in the territory.

The Indian Government considered the constitutional changes a purely “internal matter” or “internal affair” concerning the territory of India. On 6 August 2019, the spokesperson of the Indian Ministry of External Relations declared: “India does not comment on the internal affairs of other countries and similarly expects other countries to do likewise.” In particular, India was opposed to any consideration of the matter by the United Nations Security Council. India’s permanent representative to the United Nations in New York told the media: “If there are issues, they will be discussed, they will be addressed by our courts; we don’t need international busybodies to try and tell us how to run our lives. We are a billion-plus people.” The Pakistani Government saw this differently, arguing that the situation in Jammu and Kashmir posed an imminent threat to international peace and security and required the immediate consideration of the Council. On 13 August 2019, Pakistan requested that the President of the Security Council convene an urgent open meeting of the Security Council under the item entitled “The India-Pakistan question” to consider the situation arising from the recent actions by India.

Germany, being a non-permanent member of the Security Council, thus was forced to take sides – and it took India’s side. In the first instance, Germany joined other Council members in preventing the Security Council from holding a formal open meeting on India’s action. China, which had backed Pakistan’s request for an open meeting, thereupon requested closed-door informal consultations on India’s move to change the special constitutional status of Jammu and Kashmir. Being a permanent member, such a request by China could not be denied. Thus, on 16 August 2019, the Security Council discussed the “India-Pakistan question “ – albeit informally and behind closed doors – for the first time since December 1971. Being informal consultations of the Council members, neither India nor Pakistan could participate in the discussion. China suggested that after the consultations the Security Council president make a statement to the press on behalf of the Council on the situation in Jammu and Kashmir and urge the parties to refrain from action that exacerbates tension along the line of control. Such statements, however, must be agreed upon by consensus and therefore no statement was made. It was reported that the United States, France and Germany objected to language that might have broadened the issue beyond the possibility of future bilateral talks between India and Pakistan. For Germany the priority was bilateral dialogue between India and Pakistan rather than international action.

Germany, however, went even one step further. Unlike other States, it did not just consider Jammu and Kashmir a bilateral matter between India and Pakistan but openly backed New Delhi’s position that the constitutional developments with regard to Jammu and Kashmir were an “internal issue of India”. Speaking on the eve of a summit visit by Chancellor Merkel to India, the German ambassador to the country stated on 30 October 2019:

“Both leaders can discuss anything so this issue [Jammu and Kashmir] may come up. We fully support the EU position in the matter. As was detailed by Mogherini. Our position remains that Article 370 is an internal matter for India. But we support dialogue between India and Pakistan and any restrictions [in Jammu and Kashmir] should be lifted as soon as possible.”

Interestingly, in none of her statements on the situation in Jammu and Kashmir Federica Mogherini, the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, had referred to the abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution as being an “internal matter”. On the contrary, the EU expressed its support for “a bilateral political solution between India and Pakistan over Kashmir, which remains the only way to solve a long-lasting dispute that causes instability and insecurity in the region.”

The view that the nullification of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution was an “internal matter” was reiterated 2 days later by Federal Foreign Minister Maas. Speaking with the Indian newspapers “Hindustan Times” and “Dainik Jagran” on the occasion of the fifth Indo-German intergovernmental consultations in New Delhi, the Minster replied to the question of what was Germany’s opinion of India’s conduct in Jammu and Kashmir:

“As a close democratic partner to India, it is important to us – and we have expressed this view clearly – that the rights of the local population in Jammu and Kashmir enshrined in the Constitution must be respected.

We consider this [the constitutional amendments] to be a domestic issue for India to address. At the same time, however, it is clear that decisions on Jammu and Kashmir can always have an impact on stability in the region. I have consistently pointed this out in my conversations with both the Indian and Pakistani sides. For us, it is important that no side add fuel to the fire and that diplomatic channels of communication remain open.

Irrespective of that, however, it is obvious that international terrorism must be stamped out permanently. Naturally, that goes for any type of terrorism and extremism, and is not least in Pakistan’s own fundamental interests.”

Not only did the Federal Foreign Minister subscribe to India’s position that the developments in Jammu and Kashmir were a “domestic issue” for India, he also implicitly accused Pakistan of at least tolerating “cross-border terrorism” in the region.

It is quite remarkable that Germany subscribed to the Indian position of the revocation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution being a purely “internal matter”, considering that Germany had previously acknowledged that the “Kashmir region [was] contested by India and Pakistan” and referred to the state of Jammu and Kashmir as the “Indian-administered part of Kashmir.”

The disputed status of Jammu and Kashmir has also been internationally recognized in several Security Council resolutions and remains on the Council’s agenda. On 8 August 2019, the UN Secretary-General issued the following statement:

“The Secretary-General has been following the situation in Jammu and Kashmir with concern and makes an appeal for maximum restraint.

The position of the United Nations on this region is governed by the Charter of the United Nations and applicable Security Council resolutions.

The Secretary-General also recalls the 1972 Agreement on bilateral relations between India and Pakistan, also known as the Simla Agreement, which states that the final status of Jammu and Kashmir is to be settled by peaceful means, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.

The Secretary-General is also concerned over reports of restrictions on the Indian-side of Kashmir, which could exacerbate the human rights situation in the region.

The Secretary-General calls on all parties to refrain from taking steps that could affect the status of Jammu and Kashmir.”

Against this background, the unilateral alteration of the constitutional status of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, its partition into two Union territories and its full legal integration into the Indian Union cannot be considered a purely “internal matter”.

On the contrary, India’s unilateral action constituted a violation of applicable Security Council resolutions which require the two countries “to refrain from […] doing or causing to be done or permitting any acts which might aggravate the situation.” In addition, by changing the status quo with regard to Jammu and Kashmir India has violated its obligation under the Simla Agreement which requires the parties not to “unilaterally alter the situation” pending the final settlement of the problems between them.

While taking India’s side in the Kashmir conflict may have created a favourable climate for the fifth Indo-German intergovernmental consultations in New Delhi, it has set a bad precedent in terms of international law. By declaring as an “internal matter” an act that may ultimately prove to have been intended by India as a unilateral determination of the international legal status of a disputed territory the German Government has contributed to the further weakening of international law.

Category: Territorial sovereignty